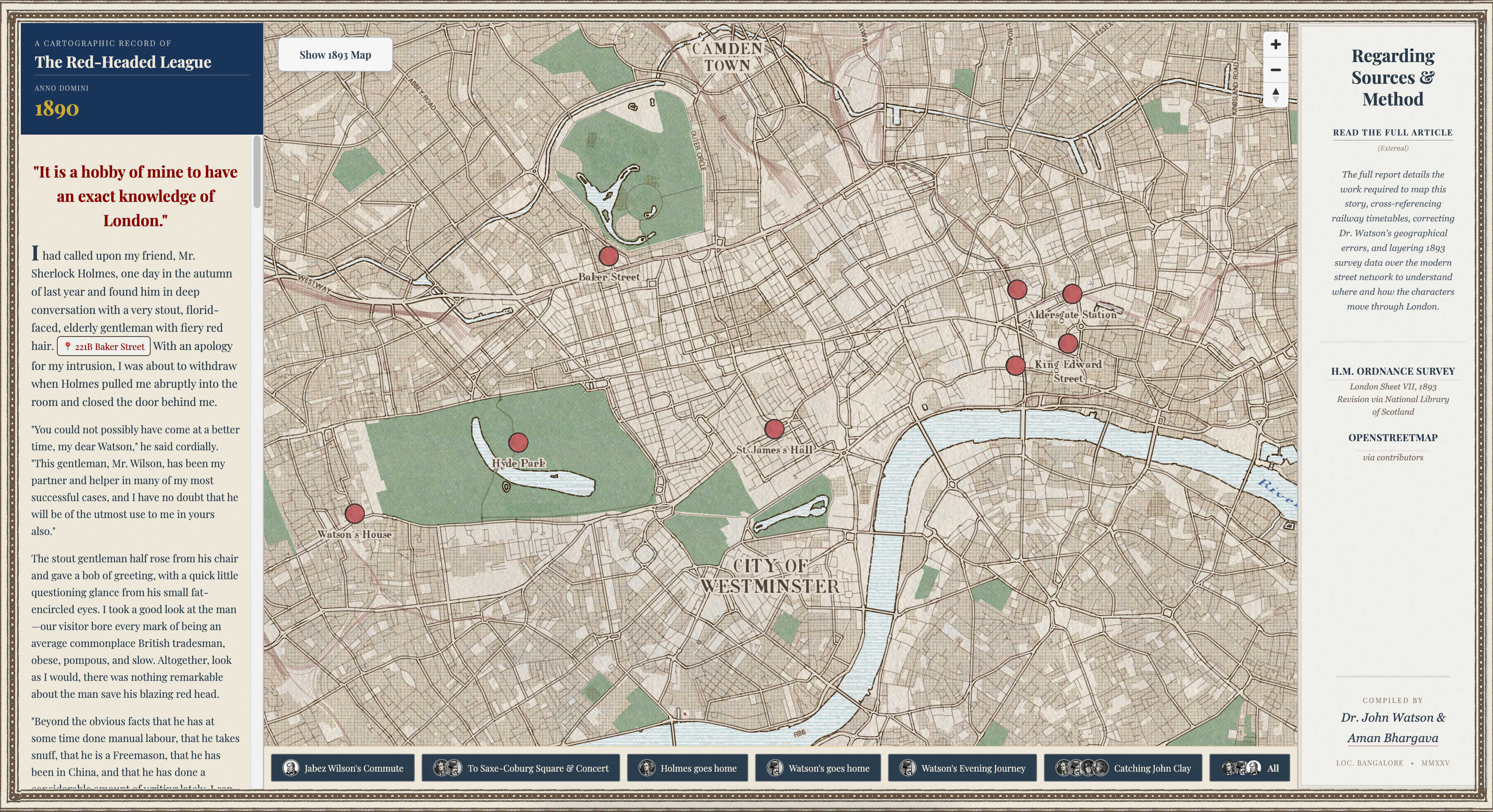

Mapping The Red Headed League

It is a hobby of mine to have an exact knowledge of London.

I mapped an adventure of the late Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, using government maps from the 1890s. I’ll get into the details in a moment, but to understand the premise, let me tell you about The Game.

The “rules” of The Game are straightforward: we treat the 56 short stories and four novels, known in these circles as the Canon (very much in Biblical reference), as historical fact. In this framework, Sherlock Holmes was a real person and Dr. Watson was his actual biographer. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is relegated to the role of “literary agent,” a middleman who merely helped publish Watson’s notes.

In his retellings, Watson often obscures dates, locations, and identities, whether through discretion or simple absentmindedness. Our goal is to resolve these resulting anomalies. To do so, we debate, and we extrapolate As the Baker Street Journal, the scholarly publication for Holmesian works, has done every year since 1949! . We cross-reference railway timetables, scrutinize Victorian newspaper reports and historical incidents, scour government records, analyze meteorological data, and, in my specific case, pore over Ordnance Survey maps to make the pieces fit.

My obsession with this is a relatively new development. Holmes and I go way back, though my entry point was strictly modern. I was a massive fan of the BBC Sherlock series while it was airing, even running a fan site for it in middle school (one of our cheesy fan-made trailers actually hit almost 2 million views!). Over the last few years, however, my interest has shifted. I’ve moved from enjoying—and eventually growing frustrated with—the modern adaptation to using the original stories as a vehicle to explore Victorian London. This allows me to mentally place myself in the city and period I’ve grown to love. To me, using these stories as an excuse to sift through this mix of geography, history, and fiction is time well spent. It informs me of contexts that neither the story alone nor any final “output” can quite capture.

You can view the full interactive map here.

This post documents how I approached mapping this classic adventure (which is, you must remember, very real).

Literary Geographies of the Canon

There are a couple of reasons why mapping these stories is such an interesting exercise.

Firstly, London’s urban structure remains very consistent with the city depicted by Conan Doyle because he set them in real places. The streets Holmes walked in the stories are, by and large, the same streets we would walk today and to me this physical persistence is very interesting. For proof of persistence, look no further than this footage from 1967 which captures the original houses where one of the Jack the Ripper murders occurred, just as they stood in 1888 (nearly eighty years after the fact). Whether in fiction or reality, a lot may have changed in London, yet very little moves.

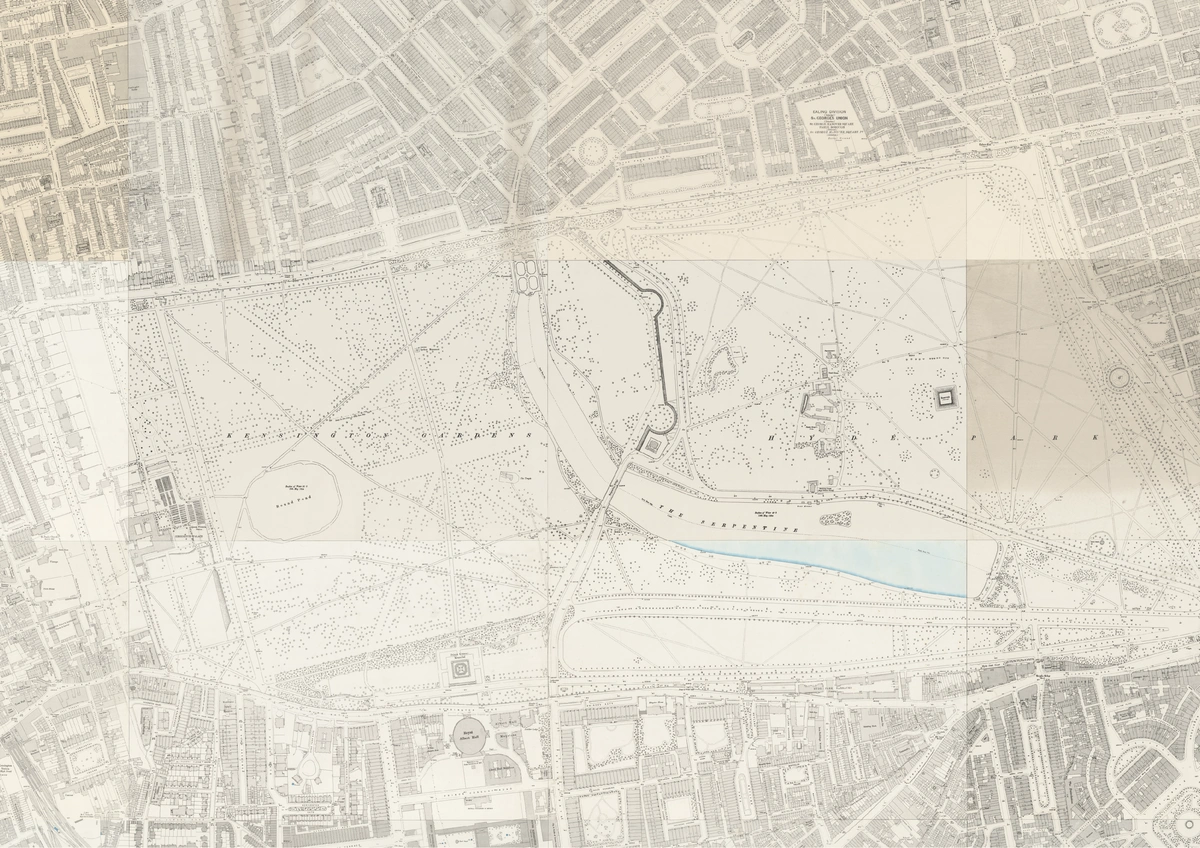

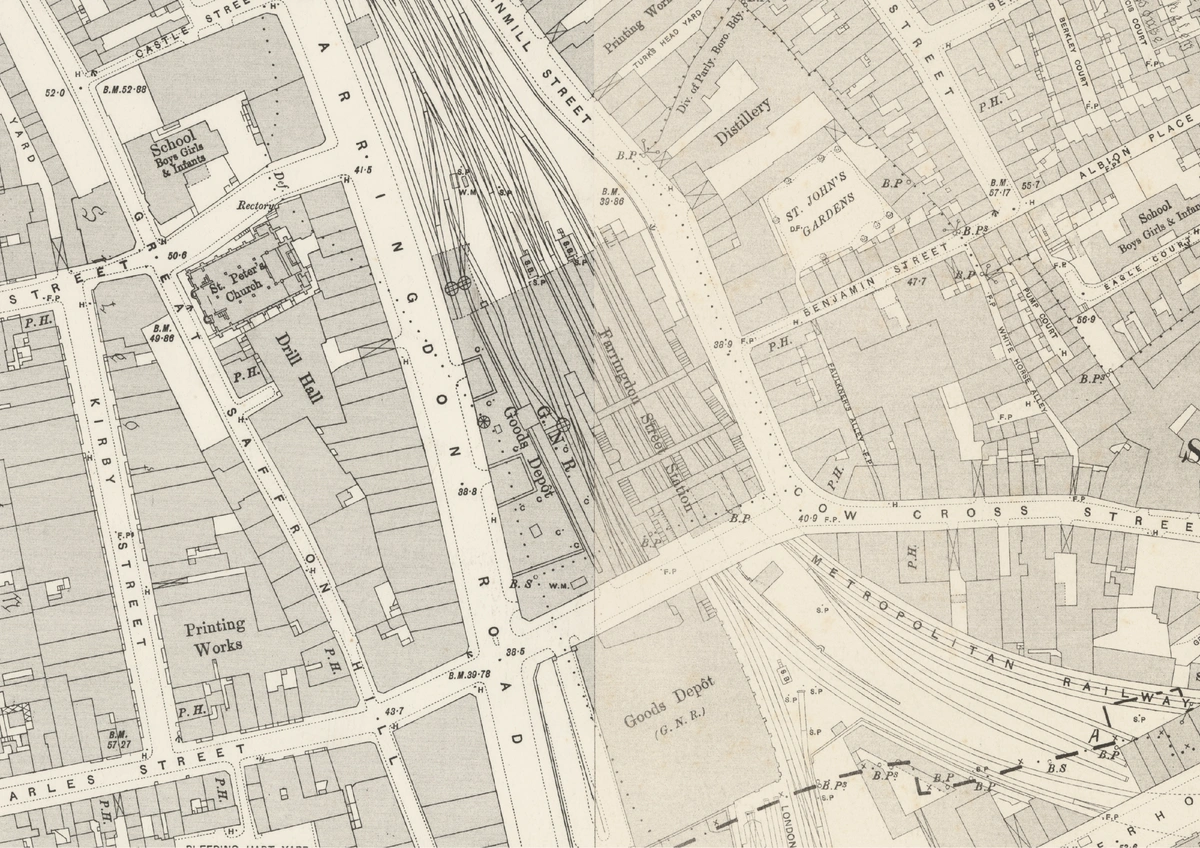

Secondly, London is perhaps the most documented city on Earth. It has been extensively surveyed across centuries including the exact decade that defines the era we’re interested in. The level of detail in these archives is staggering. We can see individual garden paths, pubs, toilets, and sometimes even inner layouts of buildings from 130 years ago. Better yet, these maps are available from the National Library of Scotland as georeferenced XYZ tiles, meaning I can load the London of the 1890s directly into tools like QGIS or MapLibre as easily as a Google Map.

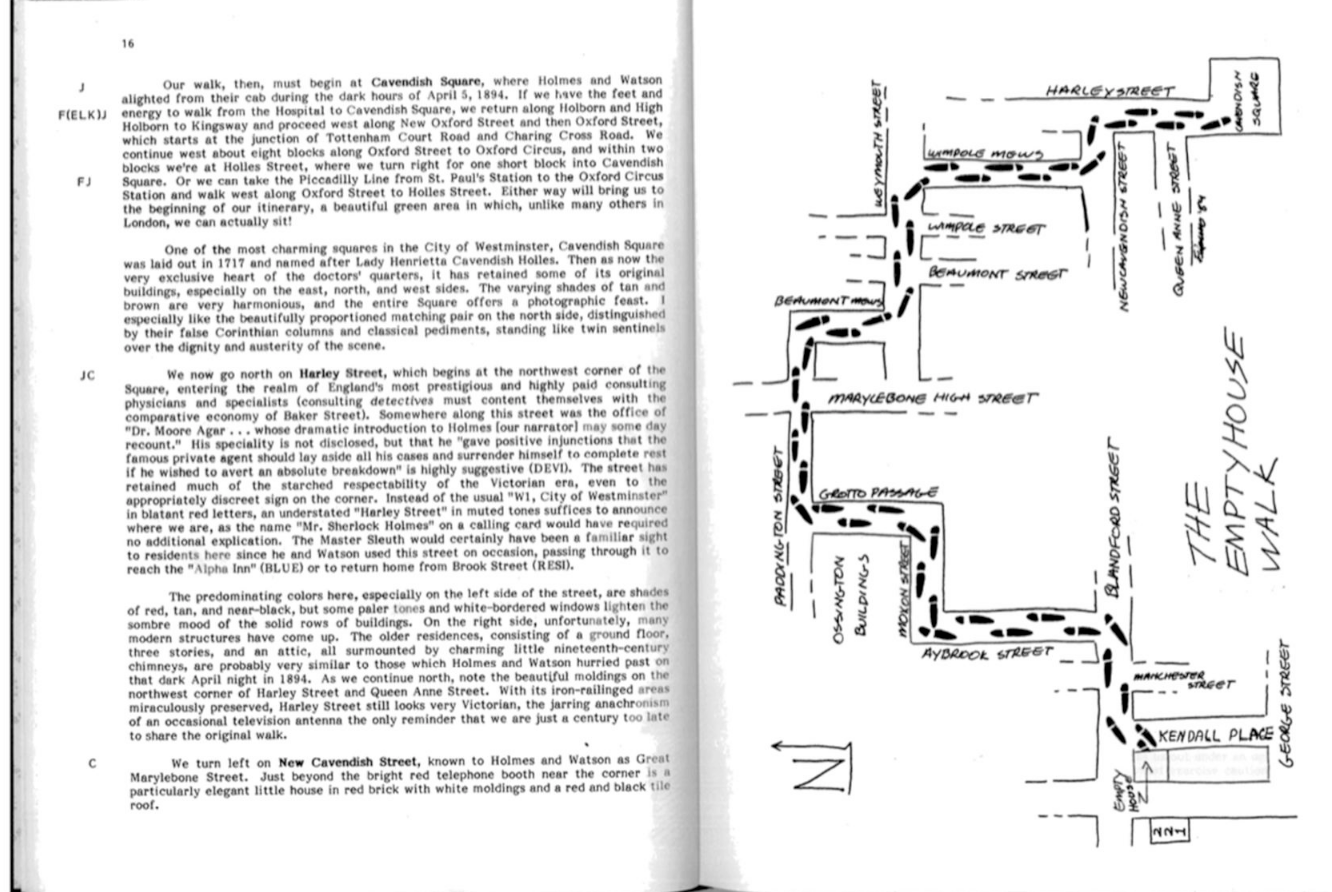

There is a problem though; a lot of the work regarding the location of these places has been done by many fans and ‘scholars’ before me. Mapping Holmes is overdone and there is almost no real “new” ground being broken on this topic. Whatever could have been discussed has been discussed. For example, here is a reconstruction of the route taken by Holmes and Watson in ‘The Empty House’ by Bernard Davies[]McLaughlin, David. ‘The Game’s Afoot: Walking as Practice in Sherlockian Literary Geographies’. Literary Geographies 2, no. 2 (2016): 144–63. https://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/68..

I’m not going to let this get me down. Instead of using their work as a cheat sheet, I’m going to try to locate these places on my own first. Only then will I consult the findings of others to see if I am on the (generally accepted) right track. Where it is impossible to ascertain a precise location from the text, I will make guesses of my own. They are, after all, as good as anyone else’s. Or at least as good as they can get without being in situ.

I chose this story at random, but it turns out to be a very useful choice.

Hello! You seem to be visiting this on a phone. Like many other things in the 1890s, this webpage is best seen on a larger surface, but it has been optimized for a smaller screen too. You can toggle the “sticky” top section with the button on the bottom-right. Minimize it, full-screen it, or just ask it to get lost; whatever works for you. But I’d still ask you to reconsider the phone.

The Red-Headed League

This one is a classic. I won’t rehash every detail, but here is the case file summary necessary to understand our map. If you’d like to read the short story before or after reading this post, it is available here.

It begins with Mr. Jabez Wilson, a pawnbroker with fiery red hair, who visits Baker Street with a unique problem. He tells Holmes of an odd organization—”The Red-Headed League”—that paid him handsomely for purely nominal services, only to disappear unexpectedly.

Wilson explains that his assistant, Vincent Spaulding, encouraged him to apply for the vacancy. Once hired, Wilson’s sole duty was to sit in an office from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM every day and copy out the Encyclopaedia Britannica by hand. He did this for eight weeks until the office suddenly closed.

Spoiler alert: Holmes deduces that the job was merely a distraction to get Wilson out of his shop for four hours a day, which gave Spaulding (who was in cahoots with the notorious criminal John Clay) time to dig a tunnel from the pawnbroker’s cellar to the City and Suburban Bank situated near it.

What time is it?

In Sherlockian studies, the matter of chronology of the cases is one of the oldest and most debated topics. The first serious scholarship that attempted to date each case was by William S. Baring-Gould, also known as Holmes’s biographer, in 1955[]‘William Baring-Gould, 54, Dies; Sherlock Holmes “Biographer” - The New York Times’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.nytimes.com/1967/08/12/archives/william-baringgould-54-dies-sherlock-holmes-biographer.html.. He would set the stage for decades of debate regarding Watson’s often contradictory timelines.

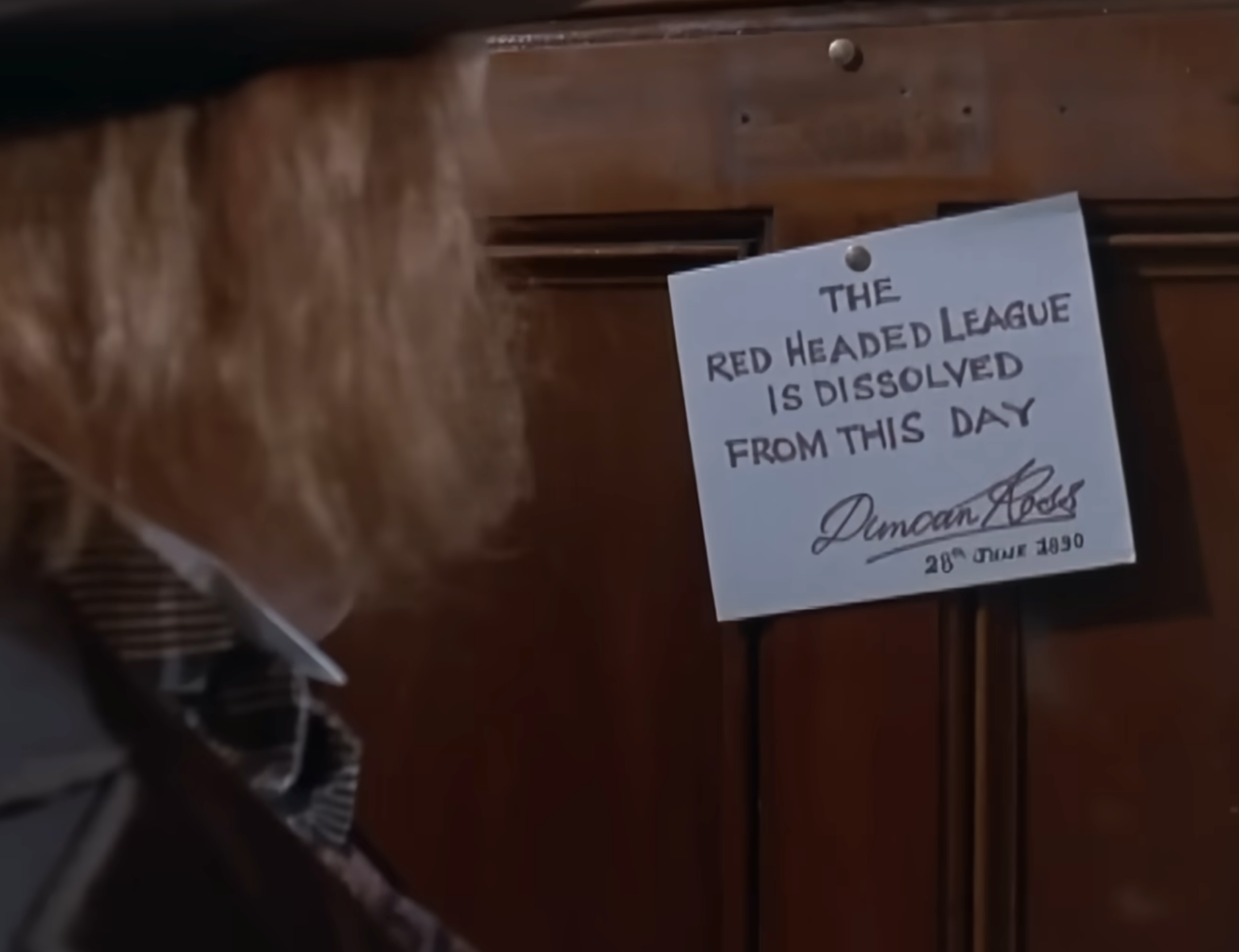

However, The Red-Headed League is the easiest case to pin down, solved by the very notice that Jabez Wilson finds tacked to his office door: “THE RED-HEADED LEAGUE IS DISSOLVED. October 9, 1890.”

No need for anything fancy here; we know what time it is! This matters because now we have a reference point for which year to source our maps and any other records we need to look up. We can also use this for secondary research for our next topic.

Part 1: Finding the Missing Places

I’ll start by establishing the chronology of events and the locations where they occurred. Here’s a timeline of the story, with the known locations highlighted:

This timeline helps establish each set of characters’ movements as we move through the story. Based on this, we know the definite addresses and locations of the following places:

Baker Street and where Holmes (approximately) lives.

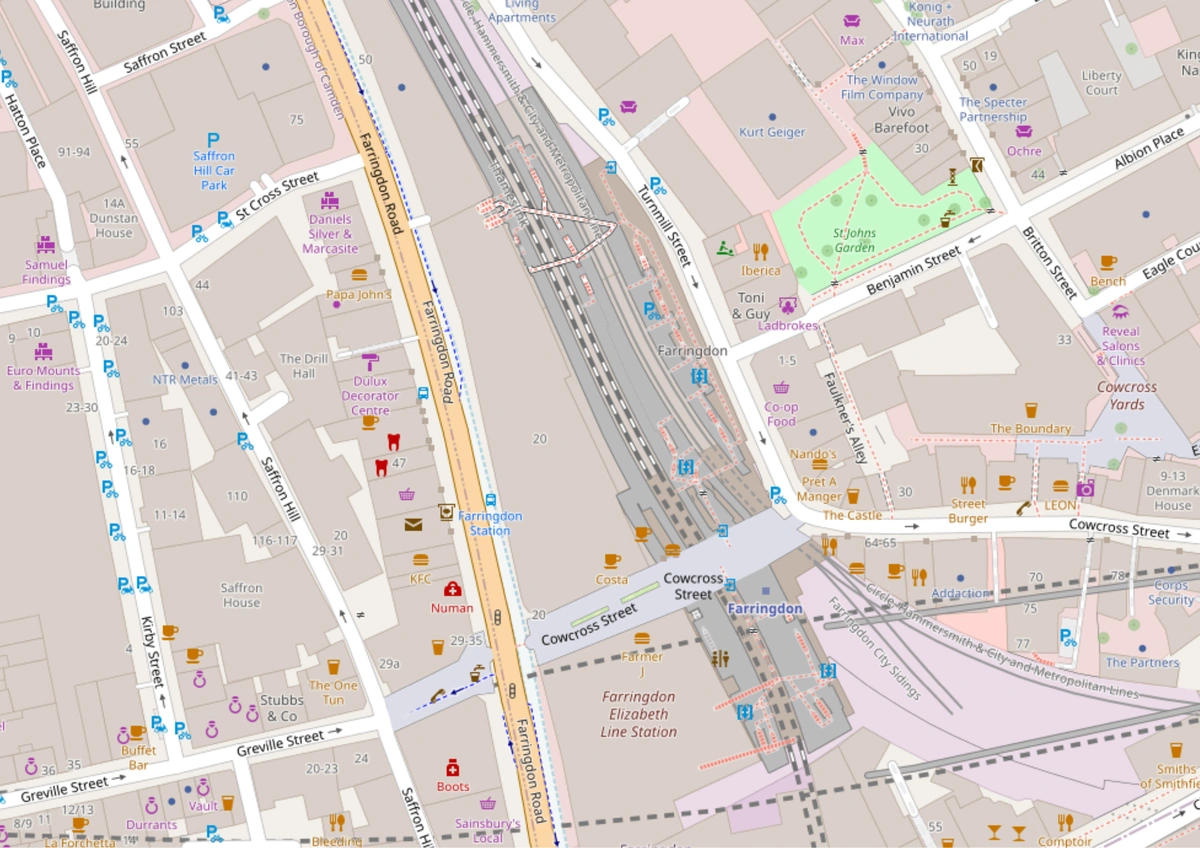

Aldersgate Station (now renamed to Barbican).

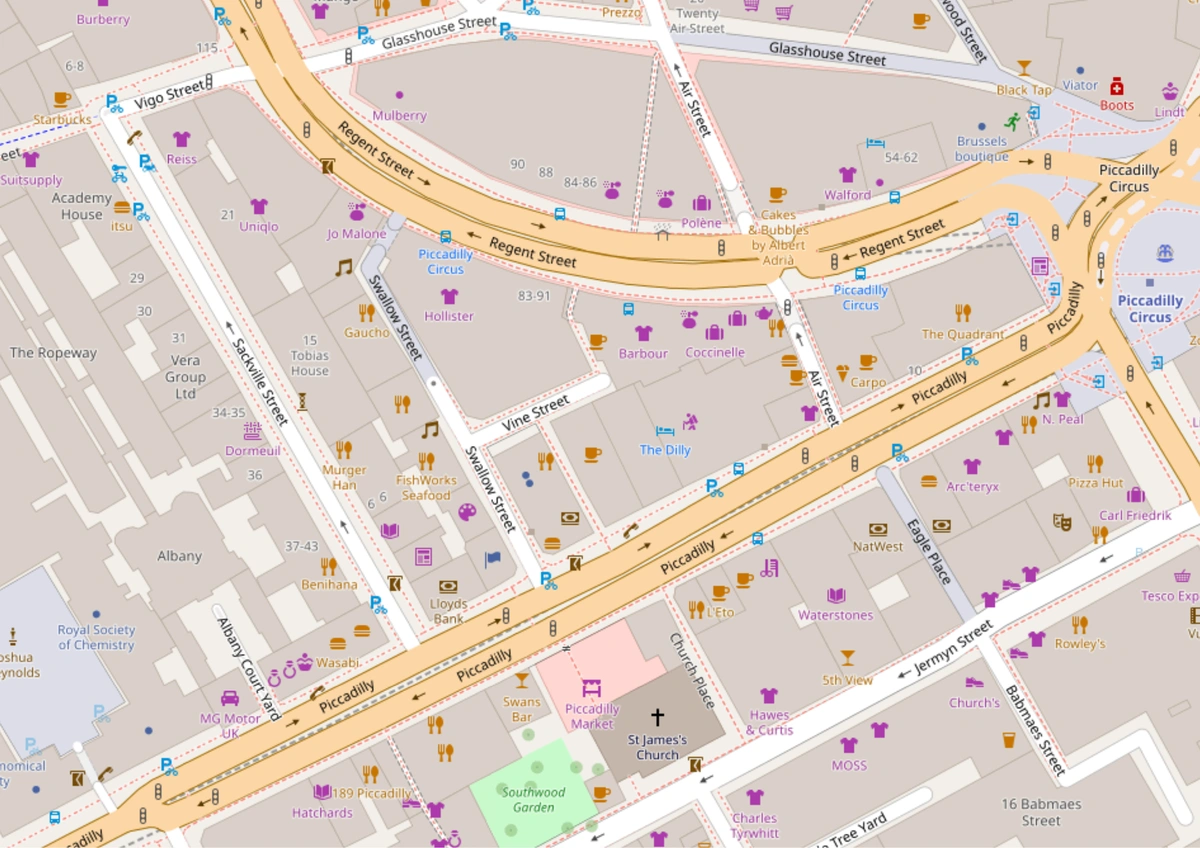

St. James’ Hall (now demolished, but easily located on the Ordnance Survey maps from the period).

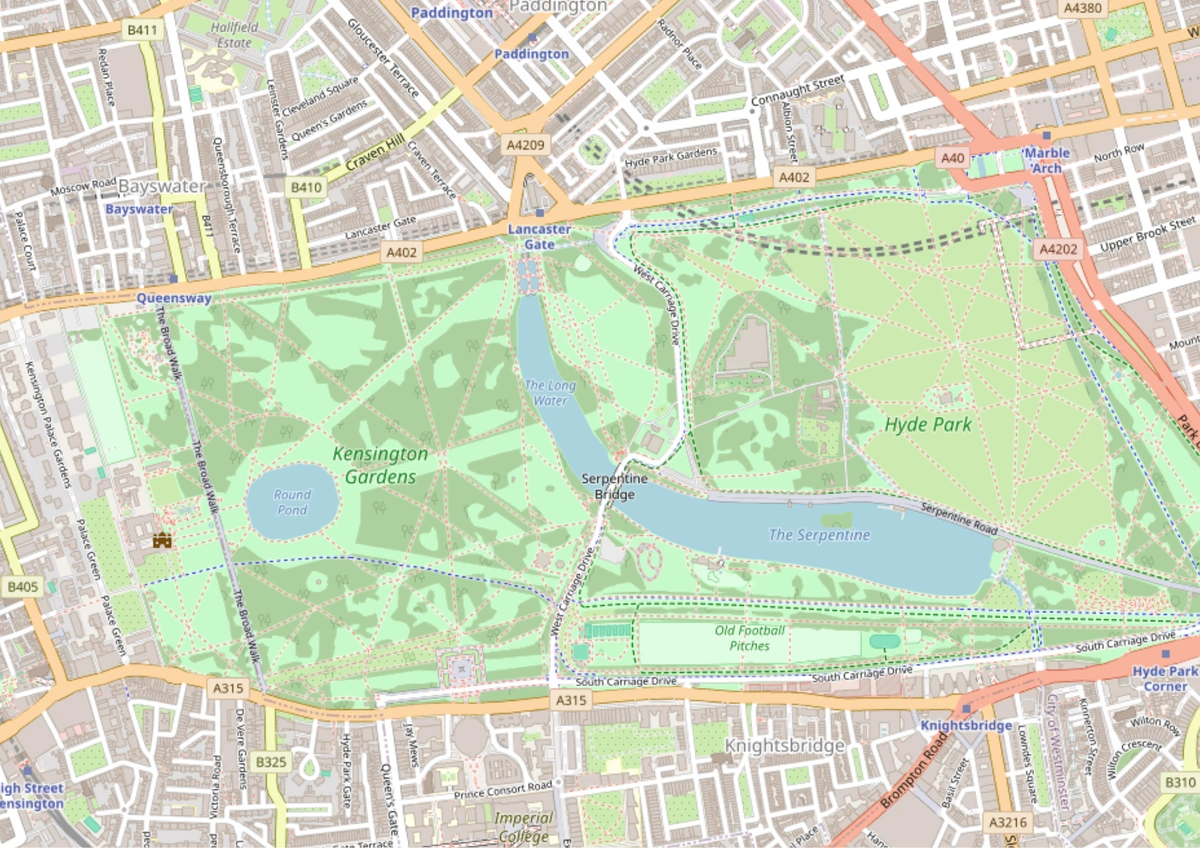

The ‘Park’ (Hyde Park, bordering Kensington) and Oxford Street.

Farringdon Street.

The two places of interest that remain are Mr. Jabez Wilson’s residence, which is also the location of his pawnshop where our villain Spaulding is tunneling under and the place of his fake “employment” where he goes every day to copy the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

How do we figure those out?

Saxe-Coburg Square

It was a poky, little, shabby-genteel place, where four lines of dingy two-storied brick houses looked out into a small railed-in enclosure, where a lawn of weedy grass and a few clumps of faded laurel-bushes made a hard fight against a smoke-laden and uncongenial atmosphere.

The problem with Mr. Wilson living in a place called Saxe-Coburg Square is that there doesn’t seem to be one. And that’s unfortunate because that is where the entire mystery unfolds. Here’s what we know:

- It is a short walk from Aldersgate Station.

- The square backs directly onto a “main artery” that conveys traffic to the North and West.

- It is a commercial area, because the surrounding businesses include a tobacconist, a newspaper shop, a vegetarian restaurant, and a carriage-building depot.

Charterhouse Square

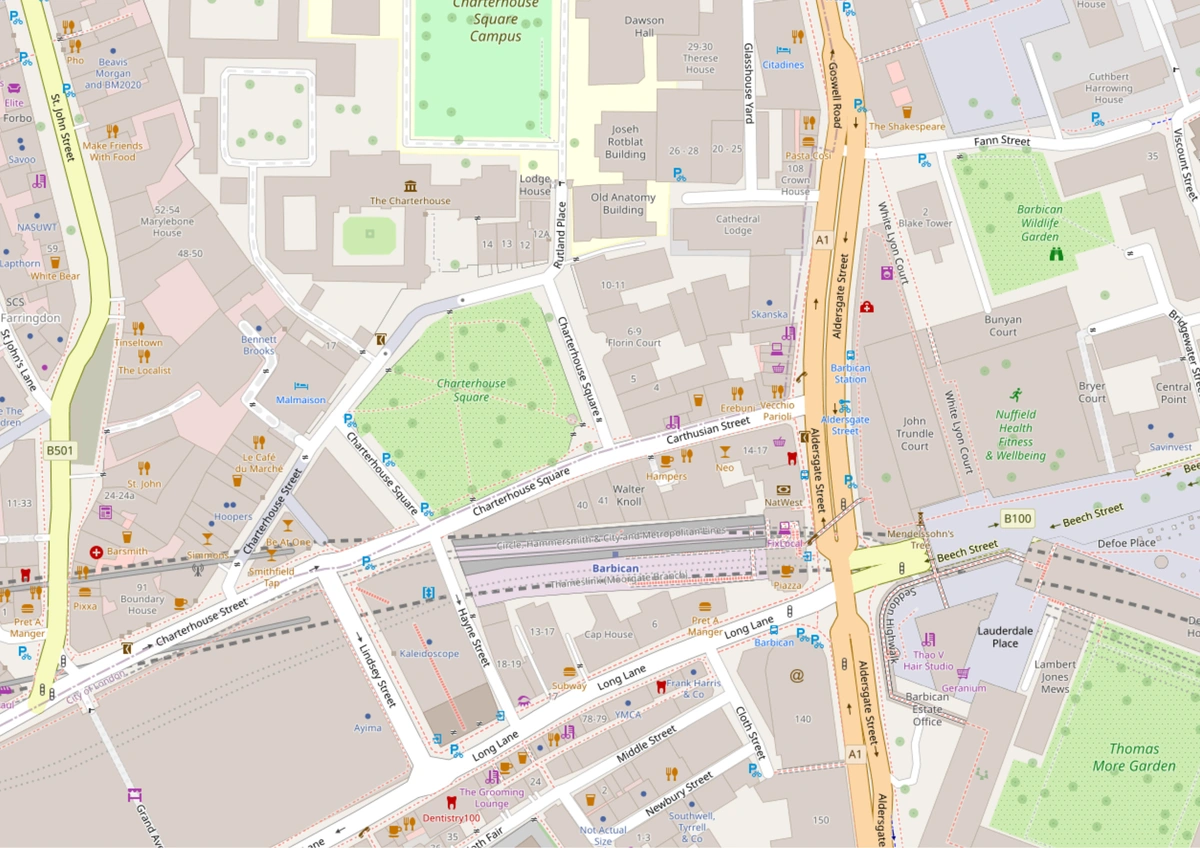

I started off by looking for Aldersgate station, which has now become Barbican. I used the Ordnance Survey layer here to see what labels I can find from that time and the only “Square” I could find within walking distance from this real landmark was Charterhouse Square. That name stands out to me because Florin Court at Charterhouse Square is the on-screen home of my other favorite detective, Hercule Poirot—it’s a small world indeed[]‘Investigating Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Florin Court - Poirot’s “Whitehaven Mansions”’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://investigatingpoirot.blogspot.com/2013/07/florin-court-poirots-whitehaven-mansions.html.. Poirot would have moved to this apartment in 1937, so he is not of much help here at the moment.

Time to look at what other people say. Writing in the Baker Street Journal, John Radford notes:

Thus, in “The Red-Headed League,” there never was a Saxe-Coburg Square so named. But Watson says it was close to Aldersgate Street Station, which did exist (it is now Barbican), so thereabouts it must have been.

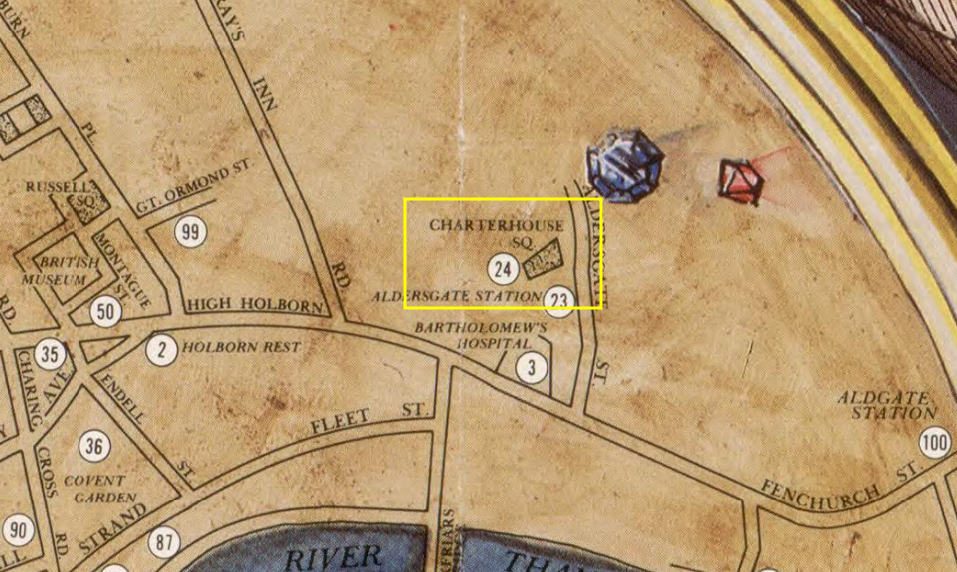

The Sherlock Holmes Mystery Map from the Aaron Blake Publishers’ Literary Map series also marks Charterhouse Square as the location of Mr. Jabez Wilson’s shop and residence.

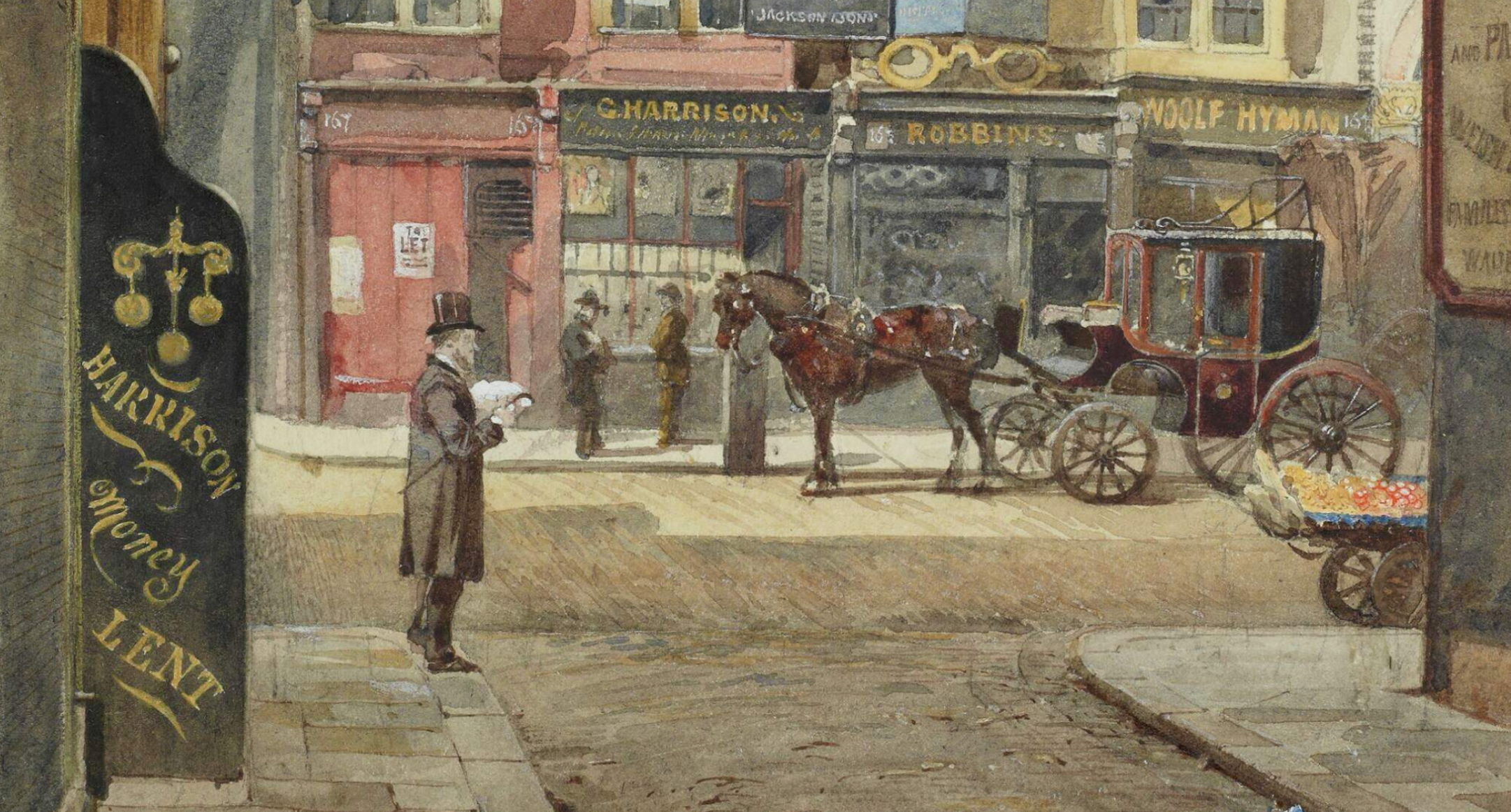

Finding this kind of stuff is fun. Since we’re really committed to this, I tried searching for photographs or illustrations made between 1880-1890s that show any of these places of interest. Funnily enough, this painting of the neighbouring Aldersgate Street features a pawnbroker’s shop very prominently[]London Picture Archive. ‘Aldersgate Street’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.londonpicturearchive.org.uk/view-item?i=15945..

So we have a Square, a pawnbroker’s shop, we’re missing a Bank. I was fairly certain we’d find one because from a letter written by Conan Doyle, we know that he used to refer to maps of London to understand where Watson’s stories took place before publishing them []‘Letter to Mr Stoddart (3 June 1890) - The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/Letterto_Mr_Stoddart(3_june_1890).. He says:

By the way it must amuse you to see the vast and accurate knowledge of London which I display. I worked it all out from a post-office map.

Looking at the Ordnance Survey map from the 1890s for this area, I find something very cool!! The map from 1893 shows “Bank”!

While the “City and Suburban Bank” is fictional, there was a bank near that exact location. In fact, until very recently, there still used to be one. It is incredible that I can look through maps from over 100 years ago and find this stuff!

Finding this bank makes our job of locating Mr. Jabez Wilson’s shop a little easier. Assuming that this is ‘The Bank’ in question, and Sherlock thumped on the pavement outside the shop to test for the tunnel, then one can assume the shop is situated directly across the road or block. We won’t try to narrow it down to the exact building; knowing that it is somewhere in this intersection is enough.

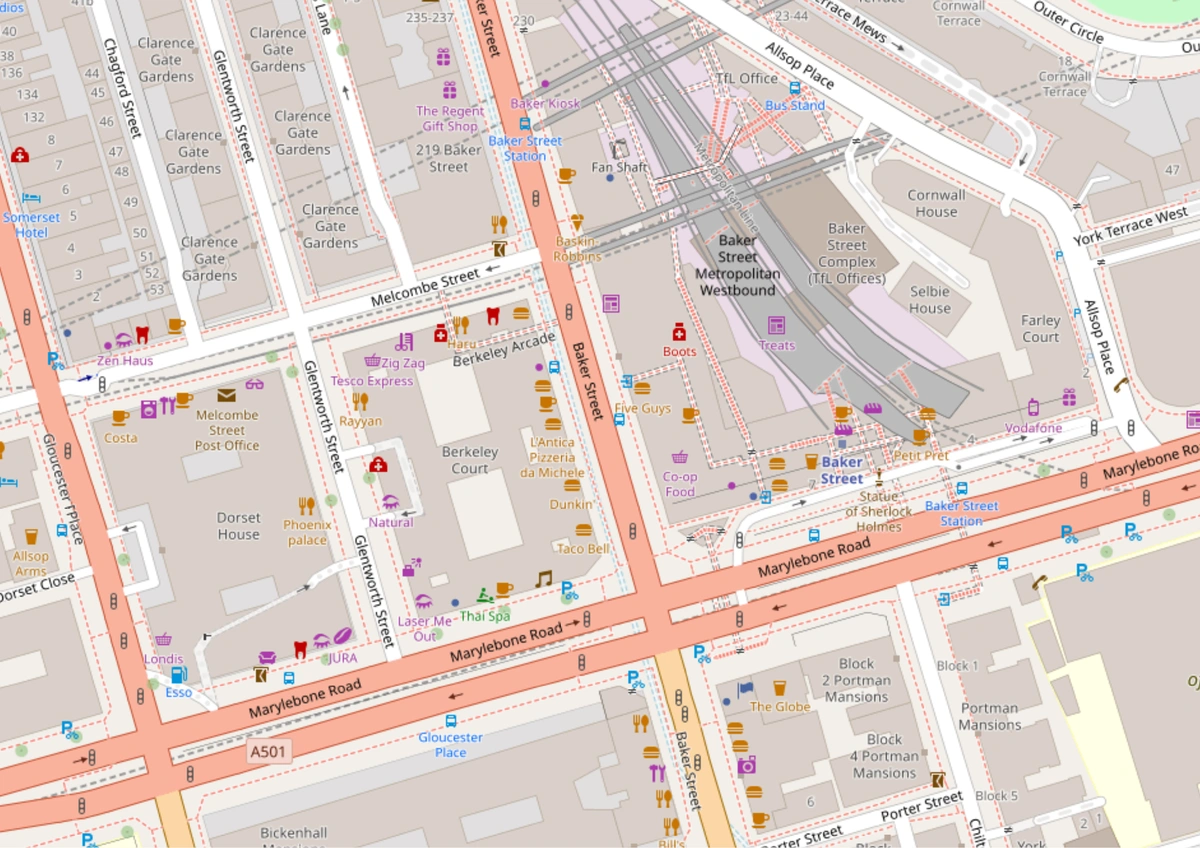

Dr. Watson’s House

At the time of this story, our biographer Dr. Watson was not sharing a flat with Holmes. In another story, The Empty House we come to know that he lives in Church Street, where Holmes surprises him by returning from the dead in the garb of an old bookseller:

Well, sir, if it isn’t too great a liberty, I am a neighbour of yours, for you’ll find my little bookshop at the corner of Church Street, and very happy to see you, I am sure.

Corner of Church Street, you say?

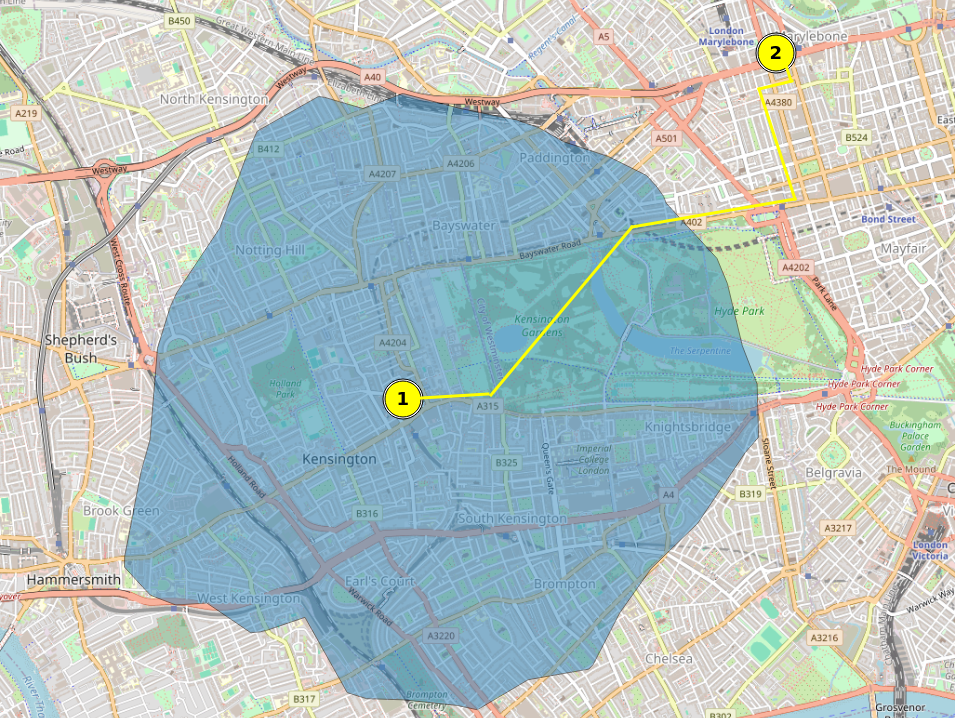

And we know he lives in Kensington, so I poked around and found that there is indeed a Church Street right there. On the night when they would catch Spaulding in the act, Dr. Watson says he leaves his house in Kensington at quarter-past nine to go “through the Park and onto Oxford Street”, which would lead him to Baker Street. This layout is geographically correct.

If he has to cut across the park to get to Oxford Street in a hurry, I suspect he lives west of the park’s lower-left corner, since that region is the only one that necessitates such a shortcut. I think it is reasonable to assume Watson lives right on the corner of the south end of the street.

He says he meets the rest of the party at around 10:00 PM but looking at the map, something felt a little off. Here is the area which can be reached from his house within 30 minutes by walk.

It would take him no less than an hour unless he was sprinting. Usually, that kind of tardiness would be inexcusable for a military man, but our bumbling narrator is what he is. Therefore we can only suppose that he reaches 221B by around 10:15 pm.

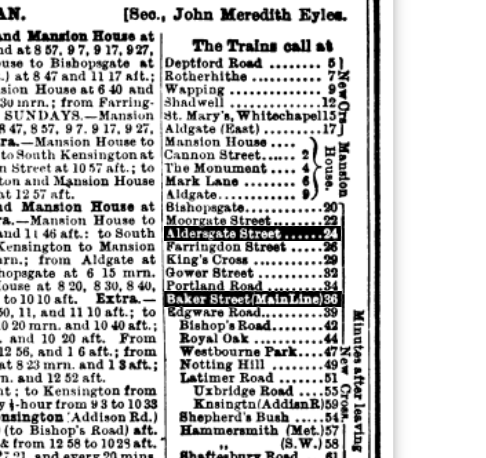

Just out of interest, I wanted to see if I could figure out if it were possible to take public-transport at this hour, and I found the railway timetable for the Metropolitan Railway from 1887! Decoding it is a bit hard. Bradshaw Railway Guides suffered from the same problems as its peers; cramming increasing amounts information in a limited amount of space and using its own shorthands for specifying time[]Esbester, M. ‘Designing Time: The Design and Use of Nineteenth-Century Transport Timetables’. Journal of Design History, ahead of print, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epp011.. From what I can tell of this mess, mrn is morning, aft is any time after noon to midnight. Scanning the page and comparing with the railway map, I guess that to go from Baker Street to Aldersgate, we’d need to look at the timings for Hammersmith to Aldsgate (heading east). I’ve extracted the relevant section below.

| Route | Late PM services |

|---|---|

| Hammersmith to Aldgate (via Baker Street) | 10:05, 10:25, 10:45, 11:13, 11:35, 11:55 PM |

| (and possibly just after midnight on some nights) |

Services on ran late into the night, and should they have wanted to take the same route as they had done at night, it was easily possible. As to why they didn’t, I cannot guess. Stealth? Build-up of fumes of the entire day made night travel unpleasant? But alas, from here to Mr. Wilson’s shop, the party travel by a cab.

I also find this funny, because almost 130 years later the metro in Bangalore has its last trains at 11 pm too. BMRCL are you looking.

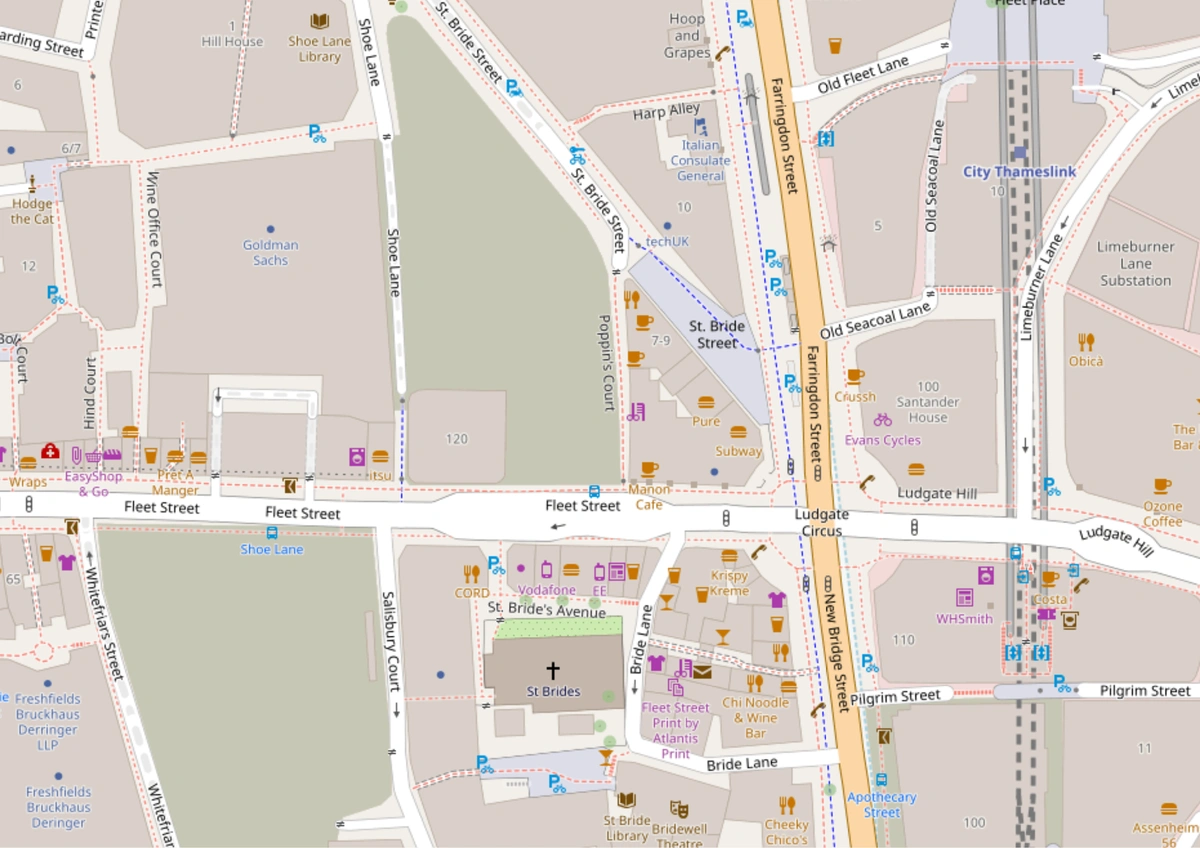

Pope’s Court, Fleet Street

This is the place of Mr. Wilson’s employment and where he’s asked to remain between 10:00 AM and 2:00 PM every day, copying out the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Fleet Street is an obvious landmark, so I can begin by locating it on the Ordnance Survey map.

I started looking for a ‘Pope’s Court’ near the street from east to west. Fleet Street has many, many courts (a “court,” as I learned, is a small lane that ends in a cul-de-sac or dead-end and is surrounded by houses), but the closest I came to finding a match was Poppins Court.

A quick pulse check and Thomas Wheeler confirms this location in The London of Sherlock Holmes, so I am satisfied.

If you’re curious about what this street might have looked like back in the day and what kind of businesses surrounded Mr. Jabez Wilson as he diligently copied the Encyclopaedia every day, don’t worry. Here is a ‘street-view’ of that section of the Strand, drawn in 1840. Notice Poppins Court in the lower-right corner? One can now perfectly imagine the environment that surrounded that sea of red-headed men when Mr. Wilson went there to apply for the post[]‘No. 15.] Fleet Street, Division I.’ Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY8132237890091496:No–15—Fleet-Street,-Division-I-..

With this, we now have all the pieces of the puzzle and can map the routes our characters might have taken.

Part 2: Transportation and Routing

The main issue with working backwards from the text is that Watson describes the events, but almost nothing about the time between them. We have the nodes, but not the edges. To understand where exactly these characters navigate and how they get there, I have to simulate the commute based on the infrastructure of 1890. Which street do they take? Do they walk? Do they hail a cab?

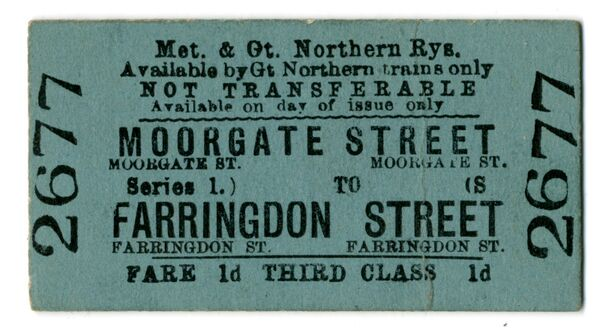

What their ticket would

have looked like[]‘Ticket; Train Ticket, Third Class Single from Moorgate Street to Farringdon Street, Fare 1d, Issued by Metropolitan & Great Northern Railways, 12/05/1900 | London Transport Museum’. Accessed 8 January 2026. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collections-online/tickets/item/2024-1223.

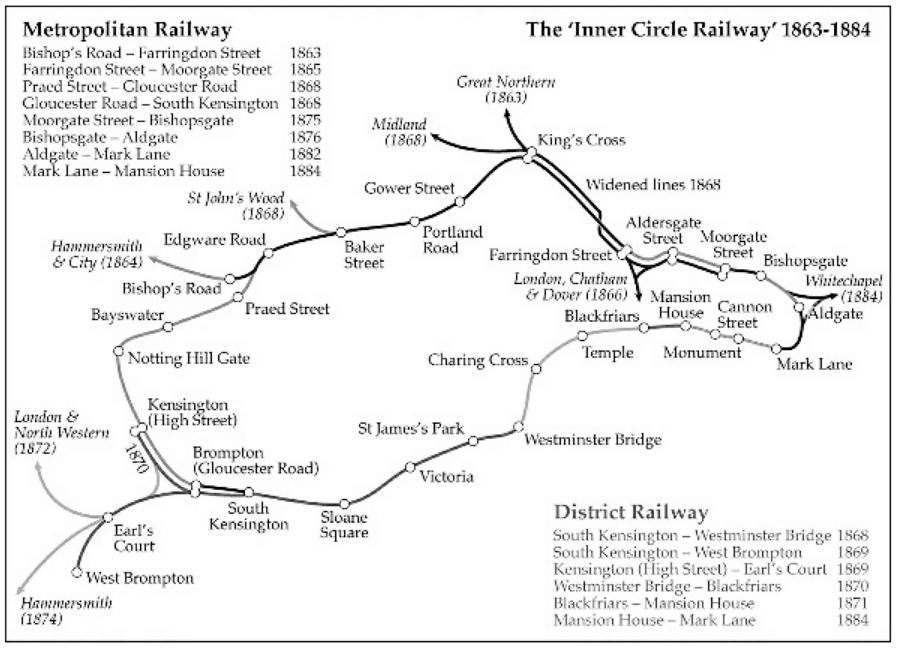

Holmes’s transport habits are usually predictable. His preferred mode is the hansom cab, though he or others will simply do things like “walk across the park” if the distance is short. Then, there is the Underground, called the Metropolitan Railway at the time. Despite the network being fairly extensive by the time 1890 rolled around (see below), and Baker Street station sitting a mere stone’s throw from his flat, Holmes almost never uses it. In fact, The Red-Headed League is the only canonical story to feature him taking the Underground.

It makes you wonder why he chose to take it this specific time and never again. As public-spirited as he was, Holmes was clearly not as pro-public-transport as we might hope, which I think is a tragic loss for the intersection of the Transit and Victorian History communities.

Underground Railways in London, 1863-1884 []Dennis, Richard. ‘Lighting the Underground: London, 1863-1914’. Sociology. Histoire Urbaine 50, no. 3 (2017): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.3917/rhu.050.0029

Based on these options, I can develop heuristics for deciding which mode of transport is being taken. If the distance is short, we can assume a walk will be good enough. For longer distances we have the option between using the railway or a hansom cab. Keeping in mind who is travelling also helps, for example, based on Wilson’s frugal character (a man who “would not part with his money easily”), it is highly probable he utilized the Railway for his initial journey to 221B Baker Street. The Baker Street station allowed Wilson to travel from Aldersgate to Baker Street in approximately 12 to 15 minutes, a journey that would have taken nearly an hour by foot or cost significantly more in a hansom cab. I’ll give you some proof, again, right from the Bradshaw Railway guide[]HathiTrust. ‘Bradshaw’s Railway Guide 1887.’ Accessed 9 January 2026. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.319510022004750?urlappend=%3Bseq=228.:

Anyway, We can translate our options to a routing engine as:

Hansom Cabs ≈ Cars: For cab rides, I use the standard “Motor” driving profile. I assume the hansom drivers of 1890 would have found approximately the same shortest path as the algorithm today.

Foot Traffic = Walking: The pedestrian network is largely unchanged (including paths through parks), save for a few modern footbridges or underpasses which I can manually exclude.

The Underground = Transit/Rail: The network between Baker Street and Aldersgate has remained consistent since the time this adventure takes place, so we can use this profile confidently.

Once the mode of transport is established, plotting the actual path is easy. Because London has remained almost the same, the modern road network in OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a nearly perfect proxy for the Victorian one.

Part 3: Plotting the routes

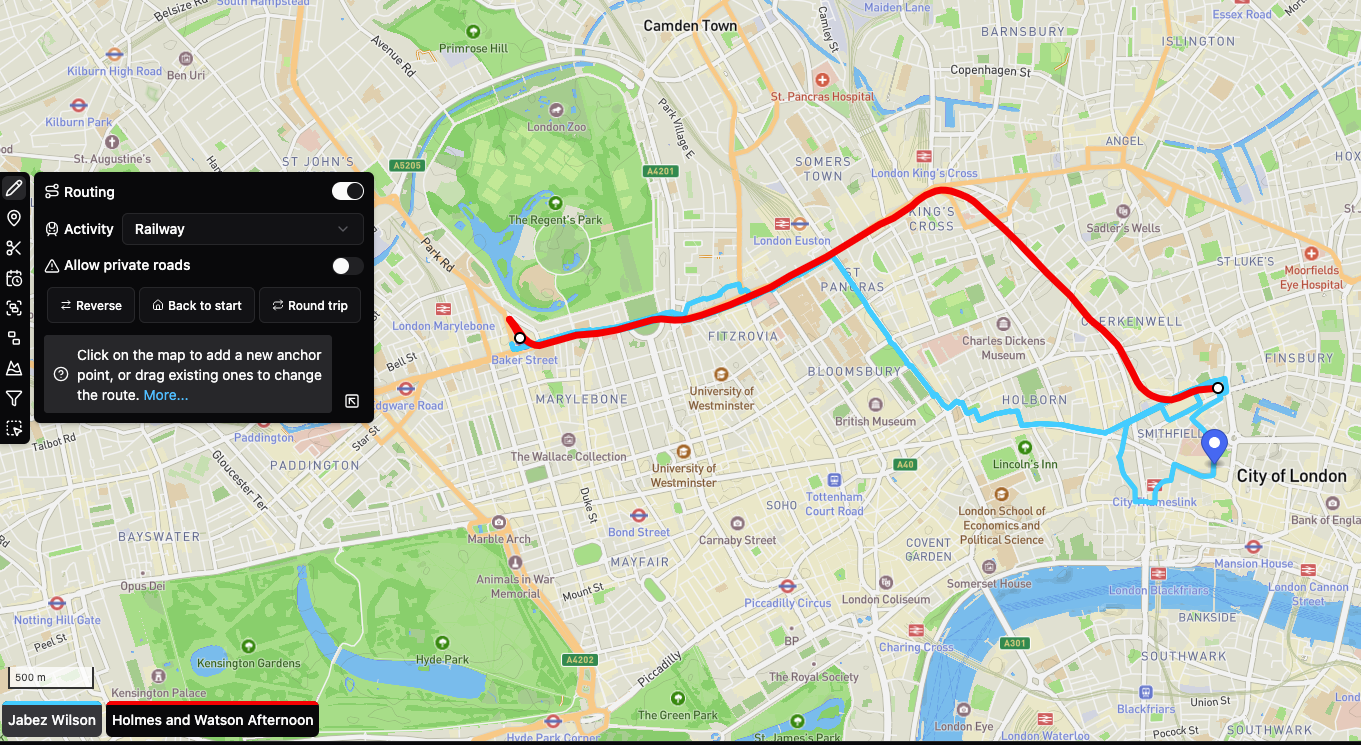

I made a note of all the places described in my timeline and began plotting them on GPX Studio, which does this in the browser, really fast. Since it does not have a driving profile, I also ended up using OpenRouteService.

I could locate the places on OpenStreetMap, create a new “file” for each character, select the mode of travel and click between points to calculate the route. There’s not that much to describe here, it is fairly straight-forward although time-consuming to set up.

The tool handles the heavy lifting. I drop a pin at somewhere in Baker Street and another at St. James Hall, and the engine calculates the most logical route between them which I can then edit. If the algorithm avoids a street because it is a one-way system in 2026 or goes through streets that didn’t exist then, I manually adjust the trace to reflect the network from the Ordnance Survey map.

Now we have our nodes and the best guestimates of our edges! I exported all of our characters from GPX Studio and cleaned their tracks up in QGIS using the Ordnance Survey basemap. This was all exported into geojsons for putting it up on MapLibre.

Click through each route below to see the character movements throughout the story:

Is it just me or does the outline of the ‘All Characters’ route look like a Persian slipper?

Making the map

Since you’ve made it this far, here’s a quick peek under the hood.

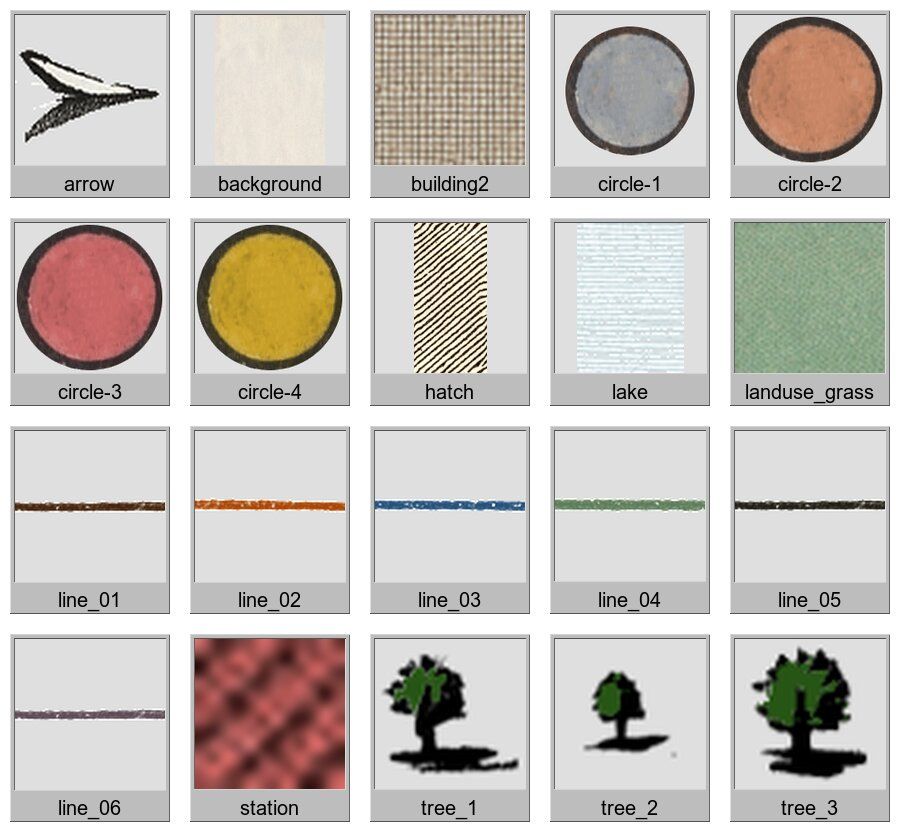

A period like the 1890s deserves a map that looks and feels the same. Getting the hand-drawn map feel has always been elusive to me, especially since I would rather not use MapBox (open-source blah blah) despite the jazz it provides. Would it be possible with open-source tools? Fortunately, I found this excellent example on recreating the Cassini style of maps in (you guessed it) MapBox from over 7 years ago. Today, it is directly compatible with MapLibre’s style schemas, so I cloned the repository and made it work with my mapping set-up with a little help from Claude. No proprietary dependencies.

However, copying the exact same style is no fun. Also, it doesn’t even have the required styling for railways, parks and other elements that I wanted to annotate. Digging a little more through David Rumsey’s map archive for things to magpie from, I assembled my own map sprites (this image was made with ImageMagick btw):

For example, the best way to make a vintage grass style is to literally snip out a section of grass from an old map you find, make it seamless and use it as a pattern-fill! Lazy, simple.

The base map data comes from OpenStreetMap served via OpenFreeMap, with the historical 1893 Ordnance Survey layer served up as XYZ tiles from the National Library of Scotland via MapTiler (the only external dependency). For the custom features such as character routes and points of interest, I assembled the data from OSM and historical sources, processed it all into GeoJSON using QGIS, and then converted most of it into PMTiles using Tippecanoe. PMTiles is a nice single-file format for vector tiles that means I don’t need to run a tile server for a backend; everything loads from a static file. Fonts come from Kenneth Field.

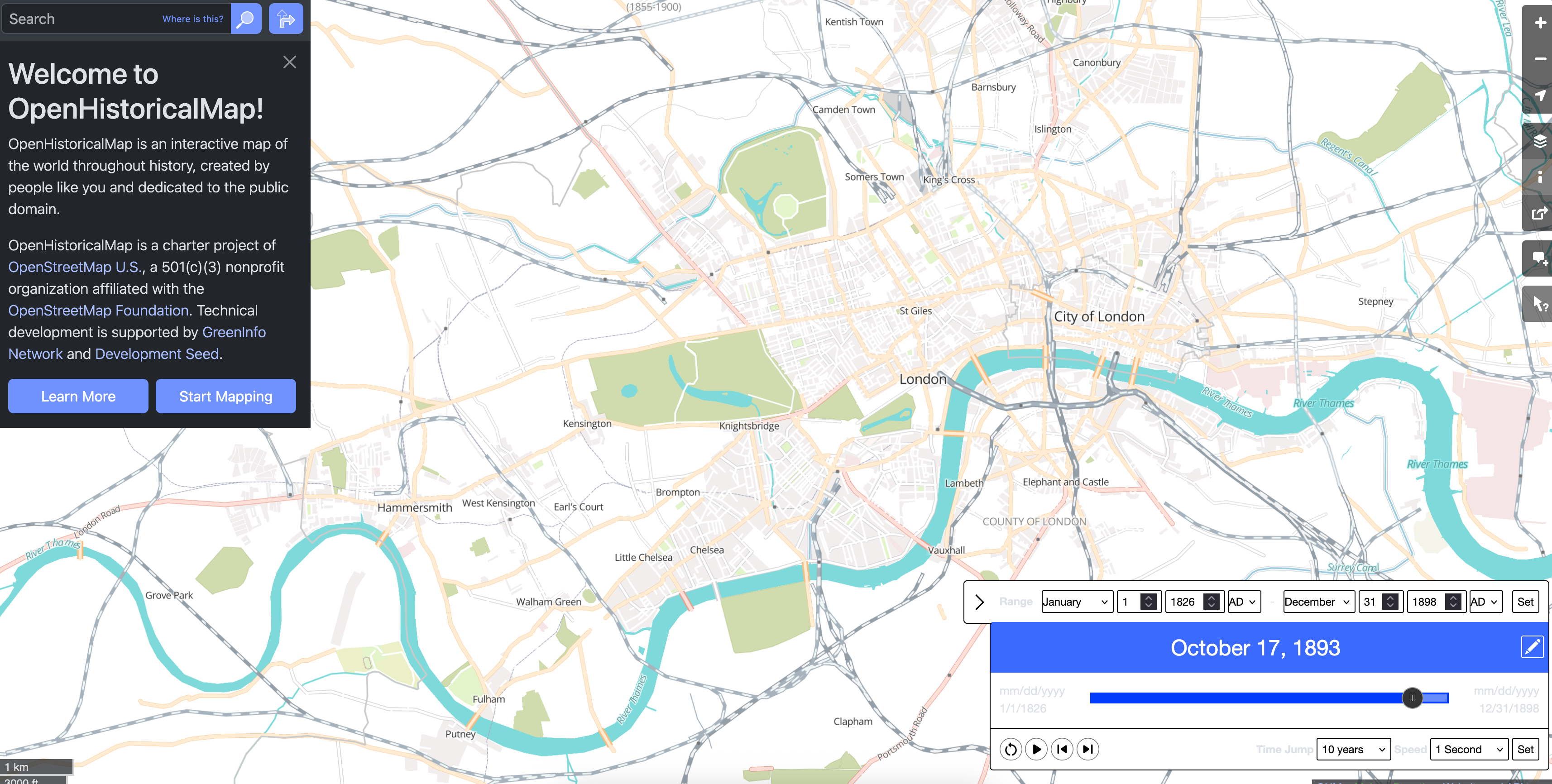

The most important, but subtle, requirement of this area are the railways. I didn’t want to pull modern railway lines here and try to keep it as accurate as possible. Thankfully, OpenStreetMap nerds have created OpenHistoricalMap, where I could set a date range to show railways in this bounding-box only up to, say, 1898.[]Thanks to Vivek for showing me this neat trick. I could have used it before I spent 50 hours manually assembling that shapefile. Very cool!

The whole thing is wrapped in a SvelteKit blog with a custom scrollytelling system I cobbled together. Many more hours of tweaking, Photoshopping, debugging, delegating-to-Claude-ing, regretting-delegating-to-Claude-ing, I had what I wanted.

You can view the full interactive map here. The source code for this interactive is available here.

So there you go. This is a summary of the process, even though it’s run up to more than 4,500 words. In the process of researching this, I went down countless rabbit holes that I can’t describe here without taking 5,000 more. Things ranging from Jack the Ripper (for some reason) to figuring out the average hansom cab fare per kilometre. I found myself reading railway timetables to find the last train out of Baker Street and learning about mews, courts, and bazaars. I learnt about the construction of The Underground and its history, and the difference between Scotland Yard’s jurisdiction and the City Police’s. I went over dozens of maps, period photographs and illustrations, and writings from other Holmesians, and finally got to scratch the itch to recreate the vintage interactive map I’ve always wanted. And a lot, lot more.

But beyond the random trivia and the design challenges, I just come away from this feeling a lot richer. I won’t elaborate on ‘richer how’ because I don’t know that fully myself but I hope you know what I mean nods knowingly.

Are you a Londoner or Sherlockian who scoffed at a geographical or factual mistake in this essay? Please let me know. As I am in Bangalore and the commute is a little steep, I am forced to remain the armchair detective. Any thumping of actual pavements with a walking stick will have to wait.

McLaughlin, David. ‘The Game’s Afoot: Walking as Practice in Sherlockian Literary Geographies’. Literary Geographies 2, no. 2 (2016): 144–63. https://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/68. ↩

‘William Baring-Gould, 54, Dies; Sherlock Holmes “Biographer” - The New York Times’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.nytimes.com/1967/08/12/archives/william-baringgould-54-dies-sherlock-holmes-biographer.html. ↩

‘Investigating Agatha Christie’s Poirot: Florin Court - Poirot’s “Whitehaven Mansions”’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://investigatingpoirot.blogspot.com/2013/07/florin-court-poirots-whitehaven-mansions.html. ↩

London Picture Archive. ‘Aldersgate Street’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.londonpicturearchive.org.uk/view-item?i=15945. ↩

‘Letter to Mr Stoddart (3 June 1890) - The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia’. Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php/Letterto_Mr_Stoddart(3_june_1890). ↩

Esbester, M. ‘Designing Time: The Design and Use of Nineteenth-Century Transport Timetables’. Journal of Design History, ahead of print, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epp011. ↩

‘No. 15.] Fleet Street, Division I.’ Accessed 7 January 2026. https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY

8132237890091496:No–15—Fleet-Street,-Division-I-. ↩‘Ticket; Train Ticket, Third Class Single from Moorgate Street to Farringdon Street, Fare 1d, Issued by Metropolitan & Great Northern Railways, 12/05/1900 | London Transport Museum’. Accessed 8 January 2026. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/collections-online/tickets/item/2024-1223. ↩

Dennis, Richard. ‘Lighting the Underground: London, 1863-1914’. Sociology. Histoire Urbaine 50, no. 3 (2017): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.3917/rhu.050.0029 ↩

HathiTrust. ‘Bradshaw’s Railway Guide 1887.’ Accessed 9 January 2026. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.319510022004750?urlappend=%3Bseq=228. ↩

Thanks to Vivek for showing me this neat trick. I could have used it before I spent 50 hours manually assembling that shapefile. ↩