Bajrangi Bhaijaan in 2025 and Youtube Journalism

November 23, 2025

I rewatched Bajrangi Bhaijaan today. It has been ten years since it was released in July 2015, and probably five or six years since I last saw it. Salman Khan is usually enough to put a certain demographic of viewers off, and I used to be one of them. There is a preconceived notion of what a “Bhai” movie entails, but if you can look past the baggage of the lead actor, I genuinely believe this is one of the nicest films to come out of Bollywood in the last decade.

For those who skipped it, the story is simple. A mute six-year-old Pakistani girl, Shahida (Munni), gets separated from her mother while visiting a shrine in India. She runs into Pawan Kumar Chaturvedi (Salman), a “Hanuman devotee” (TBH, I don’t get why he needed to be this, but it’s okay) who can never lie. When he realizes the girl is from across the border, he tries going to the embassy, then to a travel agent who took the money and almost sold the child. Finally, he decides to go against all odds and to cross the border illegally and return her to her parents himself. Watching it now, a full ten years later, is a strange experience.

It is almost jarring how much India has changed outside the movie. I think the film’s earnestness is extremely endearing.

It is an idealized and simplified depiction of cross-border relations, but looking at the current state of cinema, I think that clichéd idealism matters more now than it did in 2015. In a landscape dominated by hypermasculine violence or nationalistic propaganda films, like The Kashmir Files, Pathaan, and Fighter or whatever, Bajrangi Bhaijaan’s depiction of regular people on both sides of the border feels almost radical. It’s not sophisticated politics or commentary, but it’s earnest, and I think that’s become rare. In the movie, you hear “Jai Shree Ram” spoken repeatedly as a greeting, devoid of the weaponized political associations it carries today. You see a pre-Adani NDTV playing in the background. There are scenes depicting the Samjhauta Express running between the two nations, carrying people between countries. Today, that train doesn’t run, the services were suspended in 2019. Seeing it on screen casually part of the infrastructure and the storyline feels like I am watching a movie that is far more distant than it is.

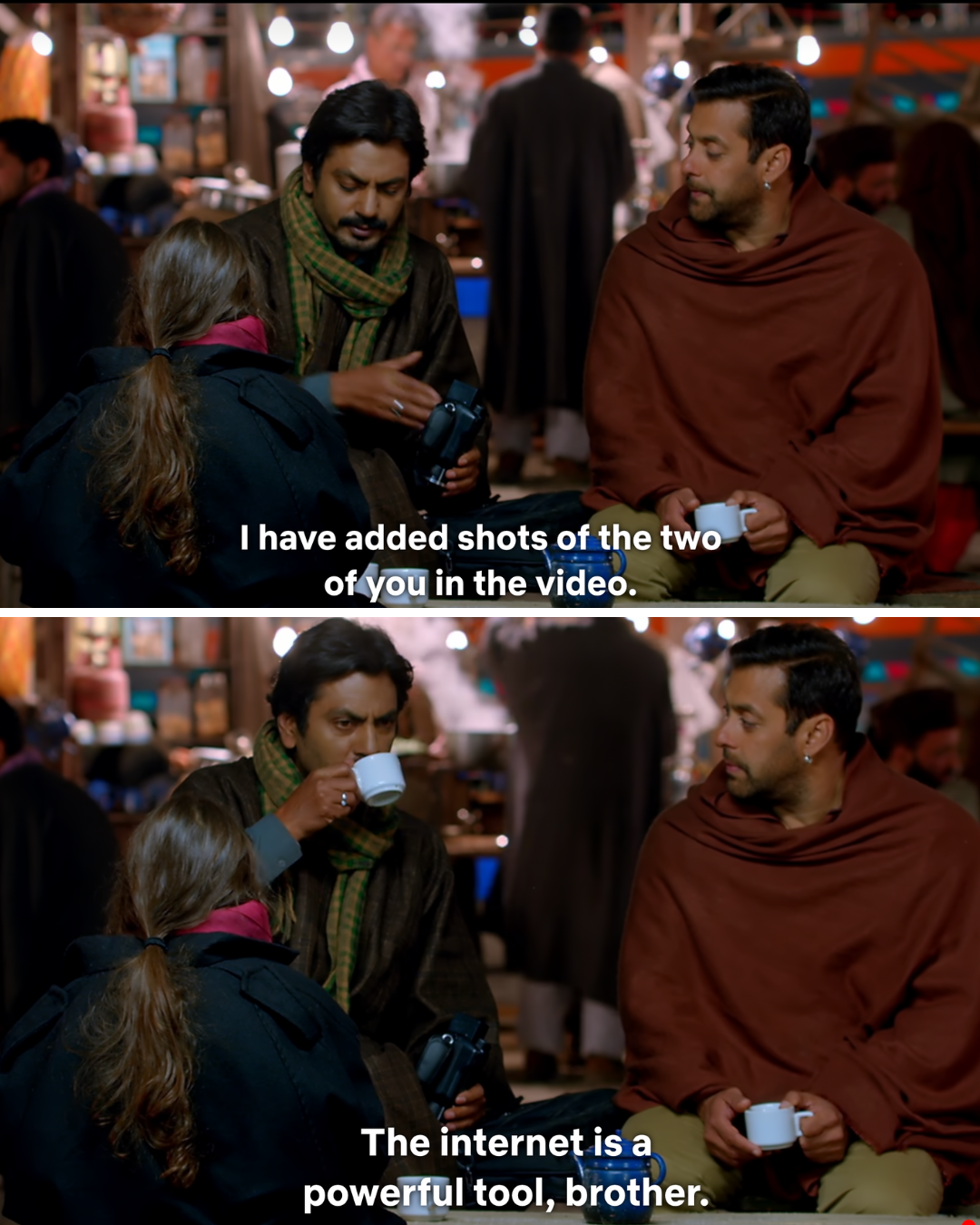

The thing that really stood out to me during this rewatch is Chand Nawab, played by Nawazuddin Siddiqui I’ve watched a lot of Nawaz over the last few weeks and he’s not disappointed in anything. I rewatched both parts of Gangs of Wasseypur, watched Black Friday, Raees, Omkara, Raat Akeli Hai, and now this. . Chand Nawab is a small-time Pakistani journalist who initially reports on Bajrangi as an Indian jasoos (spy), but later realizes that he is just a man trying to help a child meet her family again. On the run from the police in trying to help Bajrangi, he tries to take this story to the mainstream media. He calls the channels he knows, and they reject him flat out. They tell him it won’t play.

“Hate is easy to sell, but no one wants to buy a story about love.”

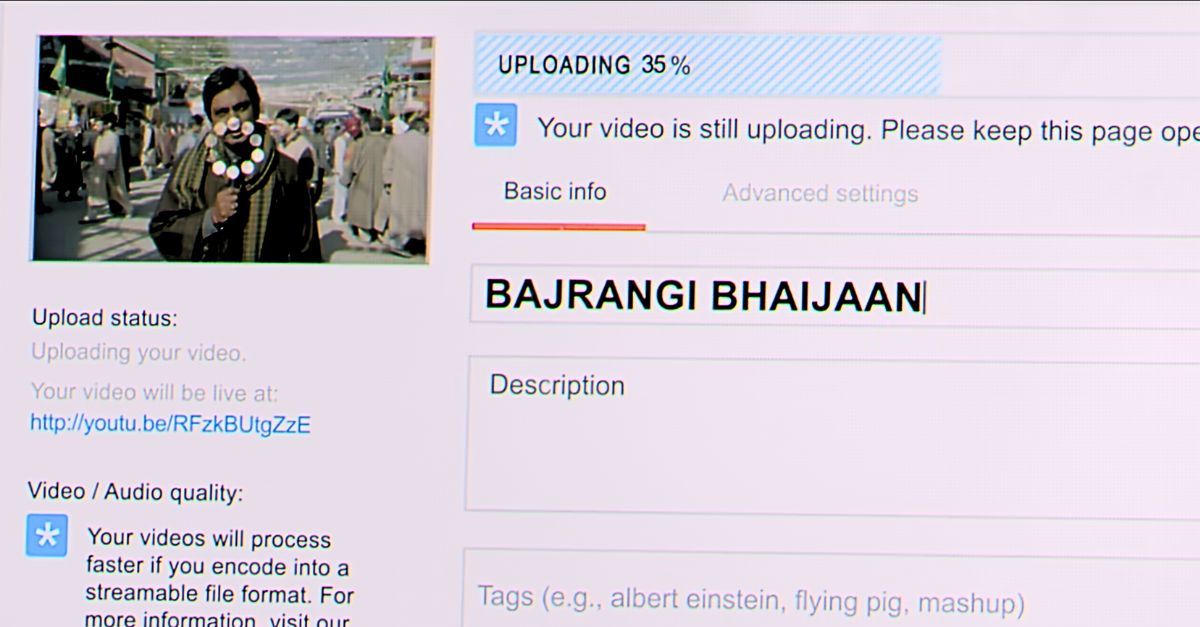

Facing rejection, Chand Nawab pivots and decides to take matters into his hands. He shoots a video on his handy cam, goes to an internet café, and uploads it to YouTube. The video goes viral. The mainstream channels, realizing that it is an undeniably powerful story which is resonating with everyone, eventually pick it up.

In 2025, this feels like an obvious trope. While there have been movies before that showed the “power of social media” in rallying support for a cause, Bajrangi Bhaijaan was perhaps one of the first mainstream Bollywood films to accurately depict this particular kind of shift for journalists. In the last decade, voices like Ravish Kumar and Barkha Dutt have left traditional networks to build massive audiences on YouTube. The reasons vary, but the realization is probably the same as Chand Nawab; traditional media establishments would rather not carry certain stories which in their view will not “sell”. Prime-time is for the Arnab Goswamis of the world, who shout and scream and manufacture outrage for people to consume; it is better to migrate to other places Here is a nice article in The Quint tracing the depiction of journalism in Bollywood through the ages. .

I think this plot-point works because film also exists right on the edge of India’s internet explosion, just a year before Jio cheapened 4G data and made it available to larger-than-ever numbers of the population. Because of this, it captures a specific moment when the internet was accessible but not yet everywhere. You see this early in the film during the film’s first song, Selfie Le Le Re, where the protagonist actually has to explain what a ‘selfie’ is. That concept that feels cringe to explain now, but it marks how novel smartphone culture was at that point in time. Chand Nawab having a handy cam but needing an internet café to upload the footage captures this transition too. All of this was very new, but internet cafés and handy cams and smartphones and people reading newspapers existed at the same time.

I love this movie. The camera work is great, the Kashmir locations are stunning, and the soundtrack is consistently good (I have listened to all the songs in the movie hundreds of times). Of course, it will have its flaws, but to me these are minor complaints against what the film does accomplish. I think it’s a very interesting watch, especially in 2025. It works not just as a great story performed by very capable actors (especially the girl who plays Munni!), but as a record of things that we have moved very far away from and some things we have moved closer to.

PS: One of the best scenes is when Nawaz’s character is introduced to us and he is trying to film a bite while a train leaves the station, constantly being interrupted by people walking within the frame. It is inspired by the real-life Chand Nawab and a clip of him doing the same thing.